In This Topic

- Types Of Chicken

- Inspection And Grading

- Hormones, Antibiotics, And Additives

- Are Meat Chickens Caged?

- Fresh And Natural

- Conventional, Kosher, Range-Fed, Free Range, & Organic Chicken

- Water-Chilled vs. Air-Chilled Chicken

- Choosing A Chicken For Barbecue

- How Much Chicken Should I Buy?

- Food Safety

- When Is Chicken Done?

- Prepping Chicken

- Whole Chicken vs. Chicken Pieces: Which Is Cheaper?

- Learn More About Chicken

- More Chicken Links On TVWB

Shopping for chicken in the supermarket or at the butcher shop can be confusing. You’ll find chicken marketed in a variety of ways—by weight, age, growing method, whole, halves, pieces, boneless, skinless, and on and on—and sold at a wide variety of prices. A range-fed chicken may sell for over $2.00 a pound, while the “regular” chicken is only 79¢ a pound.

So, which chicken should you choose for great barbecue, and how should you prep it? Well, as with most things in barbecue, there is no one answer that’s right for everyone. In the material that follows, I’ll do my best to shed some light on things so you can make educated decisions that work best for you.

Types Of Chicken

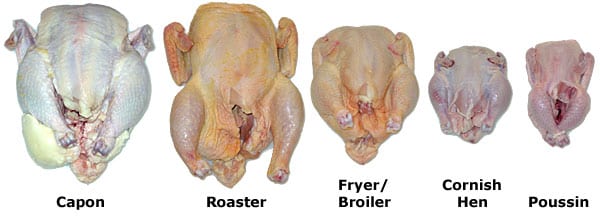

Capons are male chickens that have been castrated, 4-8 months old, weighing 5-9 pounds. Capons have more white meat and higher fat content than other chickens. They are said to be the most tender and flavorful of all chickens.

Capons are male chickens that have been castrated, 4-8 months old, weighing 5-9 pounds. Capons have more white meat and higher fat content than other chickens. They are said to be the most tender and flavorful of all chickens.

Roasters are 3-5 months old, weighing 5-7 pounds.

Broilers/Fryers are young chickens, 7-13 weeks old, weighing 2-1/2 to 5 pounds. This is the most common chicken for barbecue.

Cornish game hens are a cross between a Cornish and Plymouth Rock chicken, 4-5 weeks old, weighing about 2 pounds. Despite the name, they may be of either sex. Has a greater proportion of white meat to dark meat. Usually prepared as a single serving.

Poussin (also called spring chicken) are baby chickens, 3-4 weeks old, weighing about 1 pound. Very mild flavor with little fat. Usually prepared as a single serving.

Stewing chickens or baking hens (not pictured) are 10 months to 1-1/2 years old, weighing 4-7 pounds, and are best cooked using the methods implied by their names.

One does not typically know the breed of chicken being purchased, since it’s not disclosed by most producers.

Inspection And Grading

All chicken sold in retail stores in the U.S. is inspected for wholesomeness by either the USDA or a state agency using equivalent standards. Grading is voluntary and takes into account meatiness, appearance, and freedom from defects. The USDA describes Grade A chicken as having, “plump, meaty bodies and clean skin, free of bruises, broken bones, feathers, cuts and discoloration.”

Hormones, Antibiotics, And Additives

According to the USDA, hormones or steroids are not allowed in the production of chicken in the United States. The claim of “no hormones” cannot be used on product packaging unless accompanied by the disclaimer, “Federal regulations prohibit the use of hormones.”

Antibiotics can be used in the raising of chicken to prevent disease and increase feed efficiency. However, a withdrawal period is required to allow these substances to leave the chicken before it can be slaughtered, ensuring there are no residues in the bird. The claim “no antibiotics added” may be used on product packaging only if the producer can document that the chickens were raised without antibiotics.

The USDA does not allow the use of additives on or in fresh chicken. If chicken is processed, additives like salt or MSG must be listed on the label.

Are Meat Chickens Caged?

A common misconception is that chickens grown for meat are raised in cages. This is not true. Perhaps they’re raised in less than spacious surroundings, but they’re not raised in cages. Laying hens are the ones that live in cages.

Fresh And Natural

You’ll see the words “fresh” and “natural” used a lot when it comes to chicken. These terms have official government definitions. Here’s the USDA definition of “fresh”:

“The term ‘fresh’ may only be placed on raw poultry that has never been below 26°. Poultry held at 0°F or below must be labeled ‘frozen’ or ‘previously frozen’. No specific labeling is required on poultry between 0 and 26°F.

“…the term ‘fresh’ should not be used on the labeling of raw poultry products that have been chilled to the point they are hard to the touch.”

So in the context of chicken, “fresh” has to do only with the temperature at which it’s been maintained from the time it was processed until the time you bought it at the store. It has nothing to do with how long it’s been sitting in the display case at the store. And apparently, there’s no name to describe chicken that’s in limbo between 0 and 26°F!

USDA guidelines state that any product can be labeled “natural” if it does not contain any artificial flavoring, coloring, chemical preservative, or synthetic ingredient, and has been minimally processed. When it comes to raw chicken, “minimally processed” means it has only been handled as necessary to slaughter, clean, and make it ready for cooking.

You’ll notice that “natural” has nothing to do with the conditions under which the chicken was raised, what it was fed, how stress-free its life was, whether it ever received antibiotics, or whether organic farming practices were employed.

Conventional, Kosher, Range-Fed, Free Range, & Organic Chicken

The methods and conditions under which chickens are raised and processed have an impact on quality, pricing, and marketing. Large regional and national producers raise chickens in high volume using modern agricultural methods, in accordance with USDA guidelines, and deliver a product that is tasty, safe, and inexpensive. For lack of a better term, we’ll call this conventional chicken.

Kosher chickens are raised and processed in accordance with Jewish religious law and are clearly labeled as kosher. These chickens are hand-slaughtered rather than killed by machine and are dunked in cold water to remove feathers rather than scalded. The carcass is buried in salt for about an hour and rinsed to remove blood and impurities before packaging, in what amounts to a short brining process. Empire Kosher is one of the largest producers of kosher chickens in the United States and has a detailed description of this interesting process on its website. Of course, kosher chickens cost more than conventional chickens because they are produced in smaller numbers and require more labor to produce.

The market for range-fed, free-range, and organic chickens is dominated by small regional producers that offer their birds as a higher quality, better tasting, and more humane alternative to conventional chicken. They also command a higher price as a result.

One grower, Petaluma Poultry, describes their free range chickens as having “old-fashioned flavor because they are grown longer (9-10 weeks when marketed) and fed a high quality, flavor enhancing, corn and soybean meal vegetarian diet containing no animal fat or animal by-products.” They go on to say their chickens are grown in a stress-free environment in spacious houses and they have an outside yard in which to roam. Their chickens are never given antibiotics, and if a chicken does get sick, antibiotics are administered and the entire flock is removed and sold as conventional chicken.

Organic chickens go even further. Petaluma Poultry describes their organic chickens as being raised using “materials and practices that enhance the ecological balance of natural systems and that integrate the parts of the farming system into an ecological whole.” In addition to outdoor access and no antibiotics, organic chickens are fed certified organic feed for their entire life containing grains and soybeans grown in soil that has been free of pesticides and chemical fertilizers for a period of three years. There is an audit trail of the entire chicken’s life, from hatched egg through growing, processing, and distribution. Finally, the whole operation is certified by an outside, non-profit environmental organization to ensure everything is being done in accordance with organic principles.

Of course, producers of conventional chicken believe their products represent a better value and are just as natural, healthy, and tasty as range-fed and organic products.

Water-Chilled vs. Air-Chilled Chicken

The USDA requires that chicken carcasses be chilled to at least 40°F within 4 hours of slaughter to retard the growth of bacteria. Most processors achieve this by water chilling—immersing the carcasses in large vats of chlorinated ice water.

The advantages of water-chilled chicken are time and cost savings for the processor, which translates into lower cost for the consumer. It only takes about 1 hour for the carcasses to reach 40°F, and the process doesn’t use much electricity. The disadvantages are that the process consumes a large amount of water, and the chicken absorbs some water in the process—which you pay for in the price per pound. Studies have shown that water-chilled chicken can absorb from 2-12% of its weight on average in added water, most of it in the skin, which makes achieving crispy skin difficult.

The process of air-chilling chicken has been common in Europe going back to the 1960s, but only got started in the United States in 1998 and increased in popularity with some producers in 2008. Carcasses are sprayed with chlorinated water inside and out, then they travel through mile-long chambers in which they are blown with cold air.

The advantages of air-chilling are that less water is used, and therefore less water is absorbed by the chicken, leading some people to say these birds have better flavor and texture. Supporters of this method also believe that since these chickens are chilled individually instead of in a communal vat of ice water, they are less likely to be cross-contaminated with bacteria, although studies do not always support this contention. The disadvantages are that the process uses much more electricity for cooling and takes more time—about 3 hours to reach 40°F—so the added cost is passed along to the consumer in the form of higher prices per pound.

But to be clear, there is no scientific evidence that air-chilled chicken contains less bacteria or is safer than water-chilled chicken. In fact, research conducted by the Journal of Food Protection concluded that both water-chilling and air-chilling significantly reduced bacteria concentrations in chicken, meaning that one process was not necessarily better than the other when it comes to bacteria.

Food scientist Harold McGee, author of On Food and Cooking, is a big proponent of air-chilled chicken. In an article in the San Jose Mercury News, McGee says, “I do prefer this type of chicken. Whenever I can find them, I buy them. The basic fact that you’re not adding anything extraneous to the chicken is the most important to me. If you’re buying chicken, you want chicken—not chicken with ice water.” He goes on to say, “I don’t think air-chilled chickens will ever be the standard. But I’m sure consumers who are aware of the difference will gravitate toward them. They are just so much better.”

Choosing A Chicken For Barbecue

Life is too short and barbecue is too good to start things off with a frozen or previously frozen chicken! Choose fresh chicken whenever possible.

Buy chicken that is well within the “Sell By” date stamped on the package. If it’s about to expire, choose another bird if you can. When buying unpackaged chicken from a butcher or meat counter, ask how fresh the chicken is.

Don’t buy chicken that smells bad…it probably is. If you detect an off-odor through the plastic packaging or see excess liquid in the package, leave that bird for someone else. Any juices around the chicken should be pinkish and fairly clear, not dark or cloudy, and the less liquid in the package, the better. Look for moist skin that is creamy white or yellow in color (skin color will vary depending on natural ingredients in the chicken’s diet). Avoid dry, hard, purplish, broken, or bruised skin. The flesh should feel firm. There should not be an excessive amount of visible fat or extra skin to be trimmed off.

For barbecue, most people find that a young fryer in the 3-4 pound range works best. Cornish game hens and poussin can work well for individual servings. Avoid stewing chickens altogether.

Concerning conventional versus kosher, range-fed, free range and organic chicken, I’m not going to make a recommendation on this point. I’ve made plenty of great barbecue using conventional chicken, and I’ve made some exceptional chicken using range-fed and kosher chickens, too. Both are very good products. However, I will mention that in a blind taste test of nine chicken brands conducted by Cook’s Illustrated magazine (January/February 2002), the Empire Kosher chicken was the only “highly recommended” brand, followed by two conventional, one free-range certified organic, and one free-range chicken in the “recommended” category. Four conventional chickens occupied the “not recommended” category. Interestingly, Cook’s notes that even a “loser” in their taste test can be turned into an acceptable product through the use of brining before cooking. You can learn more about that on the All About Brining page.

Note that the price of free-range chicken can be many times higher than conventional chicken, and organic even higher than that. In the end, let your taste buds, your conscience, and your pocket book be your guide.

Now, what about whole, halves, or pieces? I prefer to cook chickens whole or whole and butterflied, feeling that whole chickens are easier to handle on the cooker than pieces and the intact carcass and skin helps keep the meat moist and juicy during cooking. Some people are very happy cooking chicken in halves, quarters, or in individual pieces, enjoying the flexibility of cooking up a smoker full of thighs only. You can also get more chicken on the cooker if it’s cut up into halves or smaller pieces, so that may figure into your decision. In the end, there’s no right or wrong answer on this point. Do what you like best.

How Much Chicken Should I Buy?

When determining the quantity of chicken needed to feed a crowd, consider that a chicken has eight pieces—two wings, two breasts, two thighs, and two drumsticks—and the breasts can be cut in half to make 10 serving pieces. I usually figure on serving four people per whole chicken if it’s the only barbecue meat being served, or eight people per chicken if served along with another meat.

Food Safety

USDA guidelines state that bacteria found in chicken are destroyed by cooking to 160°F or higher. These include salmonella, staphylococcus aureus, campylobacter jejuni, and listeria monocytogenes.

Rinsing chicken under running water is not recommended from a food safety standpoint because bacteria will splash onto your sink, faucet, kitchen countertop, clothing, and other surfaces. Proper cooking will kill any bacteria on the meat without rinsing.

Keep chicken refrigerated until at least one hour before barbecuing. Make sure to wash your hands, counters, cutting boards, knives, utensils, and anything else that comes into contact with raw chicken using hot, soapy water or a bleach solution. Avoid cross-contamination by not letting raw chicken, chicken juices, or your hands touch other foods that will be eaten raw.

Boil marinades, bastes, and mops that have come in contact with raw chicken before using them on cooked foods. Better yet, set aside a portion of the mixture for use with cooked foods and use the remainder for marinating, basting or mopping.

When Is Chicken Done?

Whole chicken and chicken pieces are properly cooked when the breast registers 160-165°F and the thigh registers 170-175°F using an instant-read thermometer.

What about the color of juices or thigh meat as a measure of doneness? According to the February 2001 issue of Sunset magazine, “The color of the juices in any part of the bird is not a good indication of whether it’s done. In the body cavity, the juices are usually pink; at the thigh joint, they are not always clear, even at 180°F.” Regarding thigh meat, “it’s almost always a little pink when you first cut into the joint, even when overcooked.” But if the thigh has been properly cooked, “the meat will lose its rosy tint very quickly on contact with the air.”

Often times, the pink color in properly cooked poultry is an indication of high pH in the meat, which fixes the pink color so that it does not break down during cooking.

Finally, don’t forget to let a whole chicken rest for 10-15 minutes before serving. This allows the juices to redistribute and reabsorb into the meat. If you skip this step, a lot of moisture will end up on the cutting board during carving, not in the meat. See Letting Meat Rest After Cooking for details.

Prepping Chicken

Many people rinse chicken under cold running water and then pat it dry with paper towels as part of the preparation process. According to USDA Food Safety & Inspection Service, it is not necessary to rinse raw poultry because proper cooking destroys any bacteria that may be present. In fact, you may just end up cross-contaminating your kitchen with splashed chicken juices.

If you’re cooking a whole uncut chicken, make sure to remove the giblets from the body cavity. Trim any large areas of fat around the cavity opening and fold the wing tips under the body to keep them from burning. Pat the chicken dry and then marinate or apply your favorite rub.

To learn how to remove the backbone and breastbone from a whole chicken so it lays flat on the grill, read the How To Butterfly A Chicken article.

If you want halves or pieces, I recommend that you butterfly the chicken first. After butterflying, just slice through the skin between the breast sections to separate the chicken into halves. For pieces, continue by cutting the leg quarter and wing from each half, then separate the leg quarter into thigh and drumstick at the joint.

Whole Chicken vs. Chicken Parts: Which Is Cheaper?

What’s more cost effective—buying a whole chicken and cutting it up, or buying chicken parts?

According to Cook’s Country magazine, to compare the price per pound of whole chicken vs. chicken parts, multiply the per pound price of the whole chicken by 1.25 (this accounts for 20% waste consisting of the backbone and wingtips). If the result is less than the price per pound of the chicken parts, then it’s more cost effective to cut up the whole chicken.

Of course, there are other advantages to cutting up a whole chicken. You’ll get consistently sized parts, they will be cut just the way you want them, and if you’re frugal, you’ll use the backbone and wingtips for stock.

Learn More About Chicken

Here are several websites you can visit to learn more about chicken:

- Foster Farms

- Empire Kosher

- Petaluma Poultry

- USA Poultry & Egg Export Council

- USDA PDF: “Chicken From Farm To Table”

More Chicken Links On TVWB

- Basic Barbecued Chicken

- Basic Marinated Chicken

- Beer Can Chicken

- Hot & Fast Chicken

- Cornell Chicken

- Cornish Game Hens – Peach Glaze

- Pulled Chicken Sandwiches

- Alabama-Style Chicken Sandwiches With White Sauce

- Boneless Skinless Chicken Breasts

- Buffalo Wings – Smoked & Deep Fried

- How To Butterfly A Chicken